History of the

Poor Boy

Poor boy sandwiches (also known as po’ boy, po-boy, and po boy) can be found in fine dining establishments, mom-and-pop diners, corner stores, and gas stations throughout Louisiana; they represent the bedrock of New Orleans and a proud working-class ethic.

The shotgun house of New Orleans cuisine, poor boys are the ambassadors of New Orleans culture, because the sandwich is as diverse as the city it symbolizes. Crisp French loaves encase virtually limitless ingredients: roast beef shrimp, oyster, catfish, soft-shell crabs, as well as french fries and ham and cheese. When the New Orleans poor boy is “dressed,” the reference has nothing to do with clothes: "dressed" means that lettuce, tomatoes, pickles, and mayonnaise are added.

There are many names for a sandwich on a length of Italian or French bread split horizontally and filled with cold cuts, cheese, vegetables, and dressing: submarine, sub, grinder, hero, hoagie, spuckie, zeppelin, zep–the list goes on. All are delicious, but an authentic poor boy is served on French bread and has distinctly Southern and working-class origins. Some may view the poor boy as a variation on a sub, which originated in Italian immigrant neighborhoods in the northeast, but the poor boy has more in common with the oyster loaf that got its start in New Orleans and San Francisco.

As with many culinary innovations, the poor boy has attracted many legends regarding its origins. However, the late Michael Mizell-Nelson, a University of New Orleans history professor, documented the following story that we’re now honored to share with you.

Bennie and Clovis Martin, brothers, left their Raceland, Louisiana, home in the Acadia region in the mid-1910s for New Orleans. Both worked as streetcar conductors until they opened Martin Brothers Coffee Stand and Restaurant in the French Market in 1922.

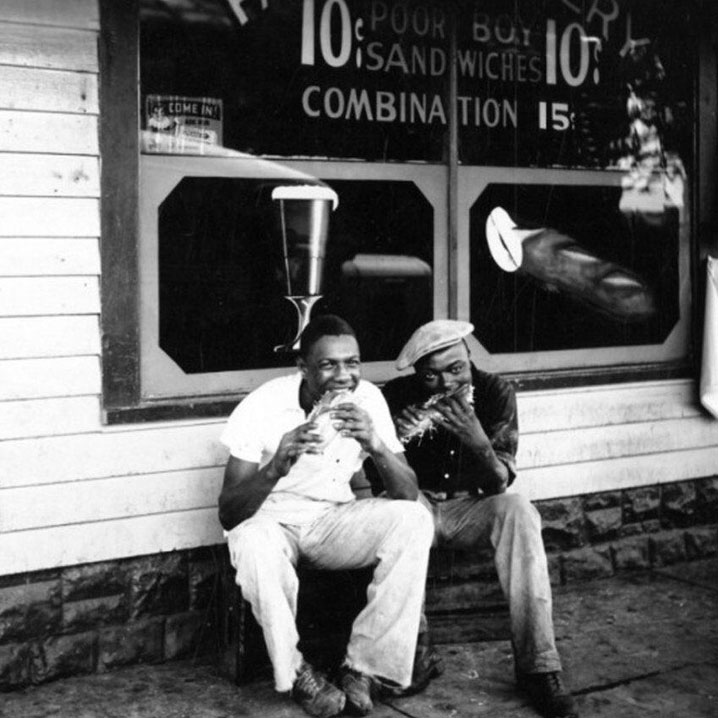

In 1929, the "poor boy" was created by the Martin brothers, who came up with the simple but hearty sandwich when the Amalgamated Association of Electric Street Railway Employees, Division 194, went on strike, sending over a thousand unionized streetcar drivers and motormen off the job and onto the picket line. The Martin brothers gave away sandwiches to the strikers that usually consisted of fried potatoes, gravy, and spare bits of roast beef on French bread.

The story goes that when a striking union member walked into their restaurant, Benny would call to Clovis, "Here comes another poor boy!" Today, hot roast beef poor boys dripping with gravy are the close relatives of these originals.

The Martin brothers soon realized that when they made their poor boys out of a traditional loaf of French bread, with tapered ends, the resulting sandwiches varied in size, and much of the loaf was wasted. The Martins worked with baker John Gendusa to develop an approximately 32-in loaf of bread that retained its uniform, rectangular shape from end to end. This innovation allowed for half-loaf sandwiches 20 inches in length, as well as a 15-inch standard and smaller ones.

The delicious bread benefitted from what chef Josh Domilese, the fourth generation to run Domilese’s Po-Boys in New Orlean, calls "the secret weapon": New Orleans humidity. People showed up in droves for the Martin brothers’ sandwiches.

But Martin Brothers Coffee Stand and Restaurant wasn’t the only poor boy game in town. Among other restaurants, Parkway Bakery and Tavern owner Henry Timothy, Sr. also added the "Poor Boy" shop to Parkway in 1929 and fed union members and conductors French fry poor boys for free. Meanwhile, Parkway was also selling the recently invented poor boy sandwich to the workers at the American Can Company. They operated twenty-four hours a day, so with the addition of the poor boy, did Parkway.

By the start of the Great Depression, the carmen had lost the strike and their jobs. The continuing generosity of the Martins as well as the size of the sandwiches proved to be a wise business decision that earned them hundreds of new customers. As the Depression worsened, many New Orleanians fed themselves and their families the famously oversized poor boy sandwiches. In the 1930s, a 20-inch half-loaf poor boy sandwich could be purchased for 15 cents.

Different types of poor boys soon developed strong followings and unique names. The Peacemaker continued to be a favorite, and has its own fascinating origin story:

Referred to as the ancestor of the poor boy, in the late 1800s, fried oyster sandwiches on French loaves were known in New Orleans and San Francisco as “oyster loaves,” a term still in use. A sandwich containing both fried shrimp and fried oysters is often called a “peacemaker.” In his book The Art of the Sandwich, Jay Harlow suggests that The Peacemaker was allegedly named for 19th-century husbands who would bring them home to waiting spouses as a preemptive apology for any (presumably) questionable behavior.

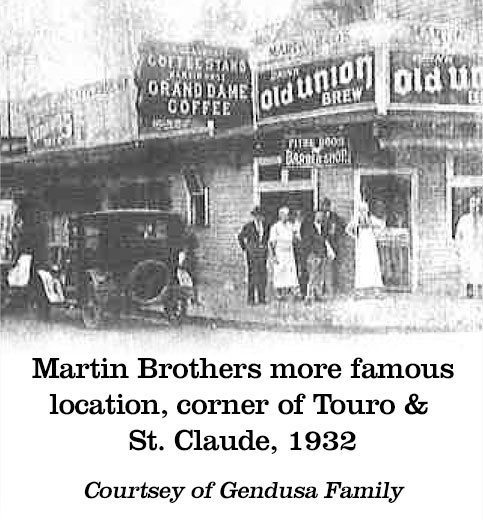

Thanks in part to their poor boy, the Martin brothers thrived. Although they had been selling “sandwiches of half a loaf of French bread generously filled with whatever one desired, from roast beef to oysters” near the old French Market in the early 1920s, it was in 1929 when they coined the name “poor boy” for versions of these sandwiches that the local media caught on and included the reference in their streetcar strike reporting–and a culinary legend found its roots.

In the late 1930s, Bennie and Clovis parted ways, with Clovis going on to develop several other restaurants throughout the city known as Martin and Son Poor Boy Bar and Restaurant. Their locations on Gentilly and Airline Highway lasted the longest. Clovis died in 1955, and Martin Brother’s St. Claude restaurant survived into the 1970s– with signs declaring the brothers as the "Originators of Poor Boy Sandwiches." By then, the poor boy/po'boy/ po-boy/po boy sandwich name had spread far beyond New Orleans.

After Parkway closed in 1993 and Timothy, Sr.’s two sons, Henry Jr. and Jake put it up for sale, Jay Nix bought Parkway in 1995 and came up with a new slogan for the business: "Parkway for Poor Boys." If you want a poor boy, you go to Parkway. Nix also changed all the branding on the building to poor boys as an homage to the 1929 strikers, because the sandwich was born of hard times and Jay wanted to honor that.

According to historian Errol Laborde, the correct way to refer to the sandwich is “poor boy” because it was created by the Martin brothers after the streetcar strikers – those “poor boys.” But whether it’s referred to as a poor boy, po’ boy, po-boy, or po boy, what everyone can agree on is that the famous sandwich holds its place in the hearts of generations of Louisiana families and its many fans around the world.

"Poor boys are a way of life," explains Parkway Bakery and Tavern General Manager and Head Chef, Justin Kennedy. "It’s like going to church. It’s like walking your dog … it’s the lifeblood in New Orleans. I’m glad to be a part of it."

We’re honored to be recognized by USA Today as serving the "Best Po’boy in Louisiana" and appreciate everyone who chooses #ParkwayforPoorboys.